May 31, 2024

I have been reading, implementing, and playing with The Curious Case of Neural Text Degeneration, a wonderful paper on sampling from language models. I want to give some background on why we sample from language models, how we can sample from them, and why nucleus sampling (or top-p sampling), introduced in this paper, works so well.

How do language models work?

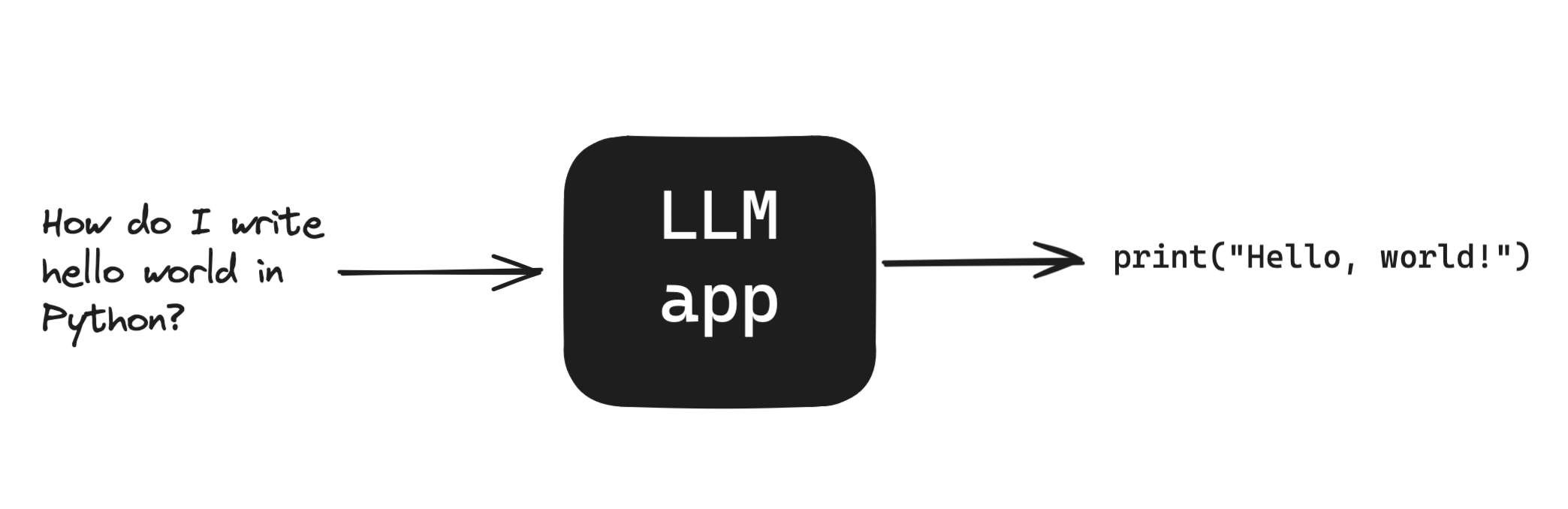

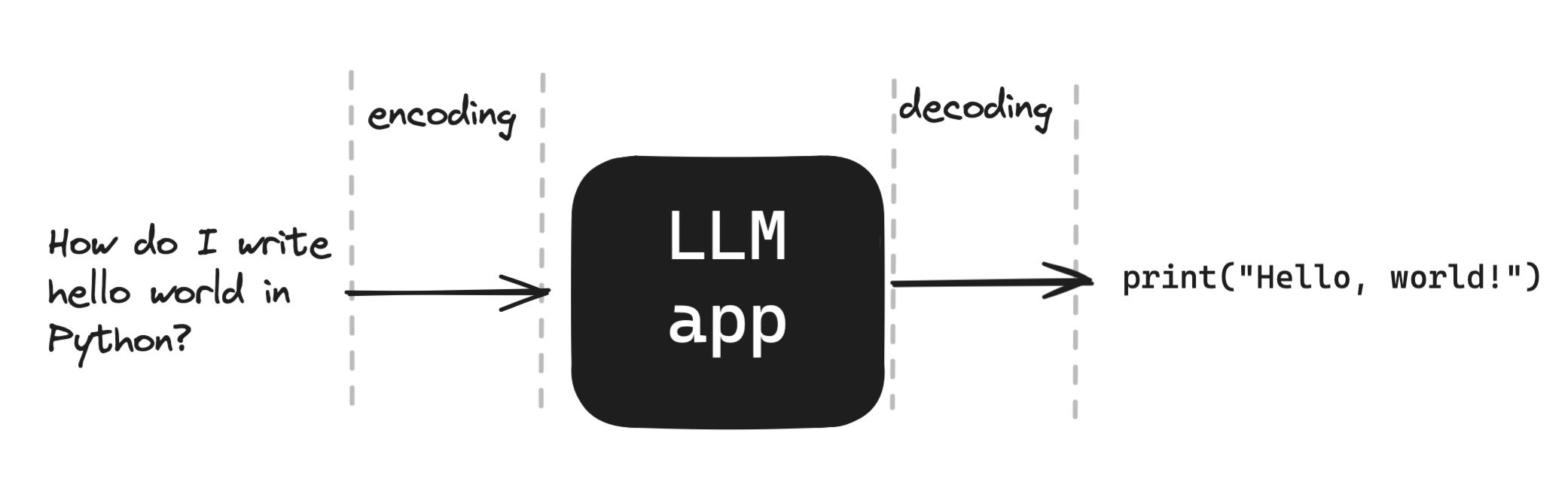

Consider a language model as a black box, much the way we might use the ChatGPT website. We send in words; we get out words.

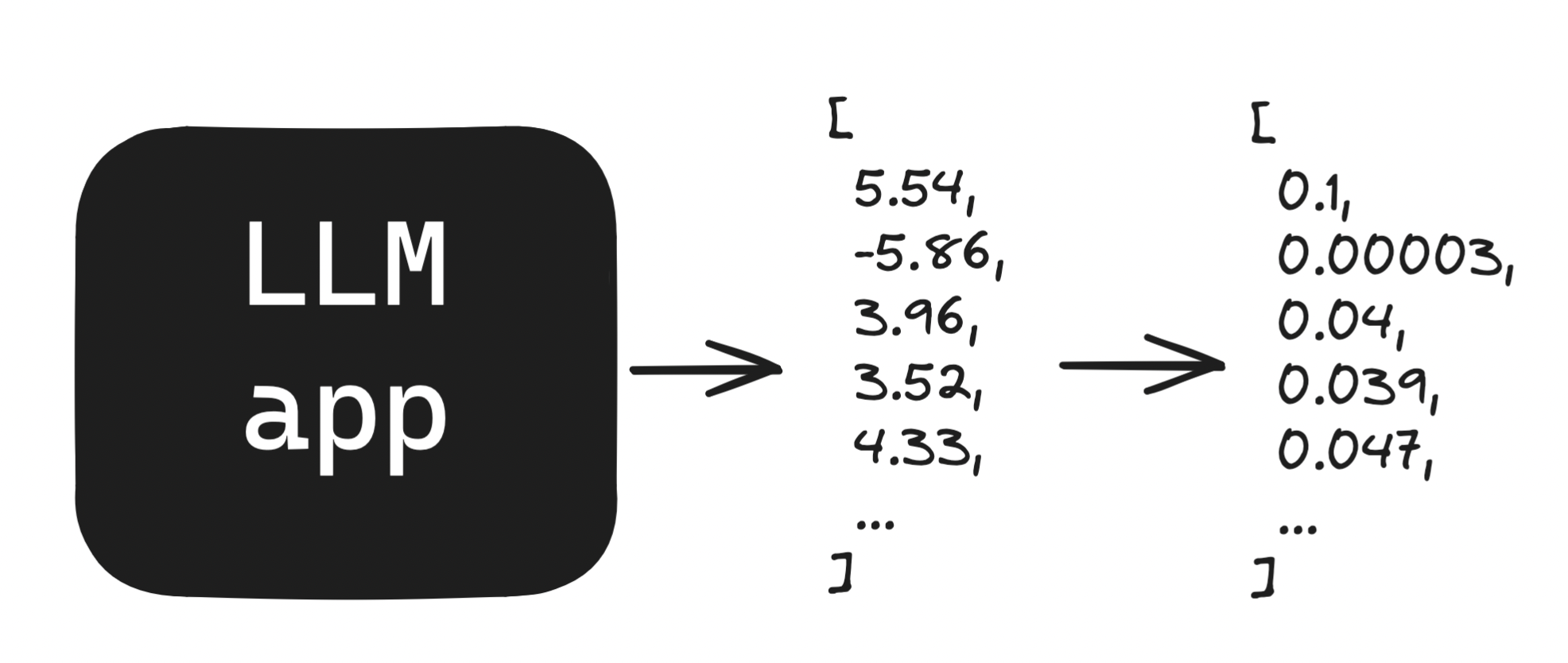

We translate our question by encoding it, or converting it to a sequence of numbers. The model outputs more numbers, which are decoded back to tokens.

ℹ️ A quick aside on terms

Encoding and decoding are overloaded terms. While they do refer to translating language (or other data) to and from model space, they also refer to translating language (like these words!) to bytes the computer can understand and back. To make matters worse, models based on the Transformer architecture - like GPT2, analyzed in this paper, and ChatGPT - contain large blocks called encoders and decoders. Yuck.

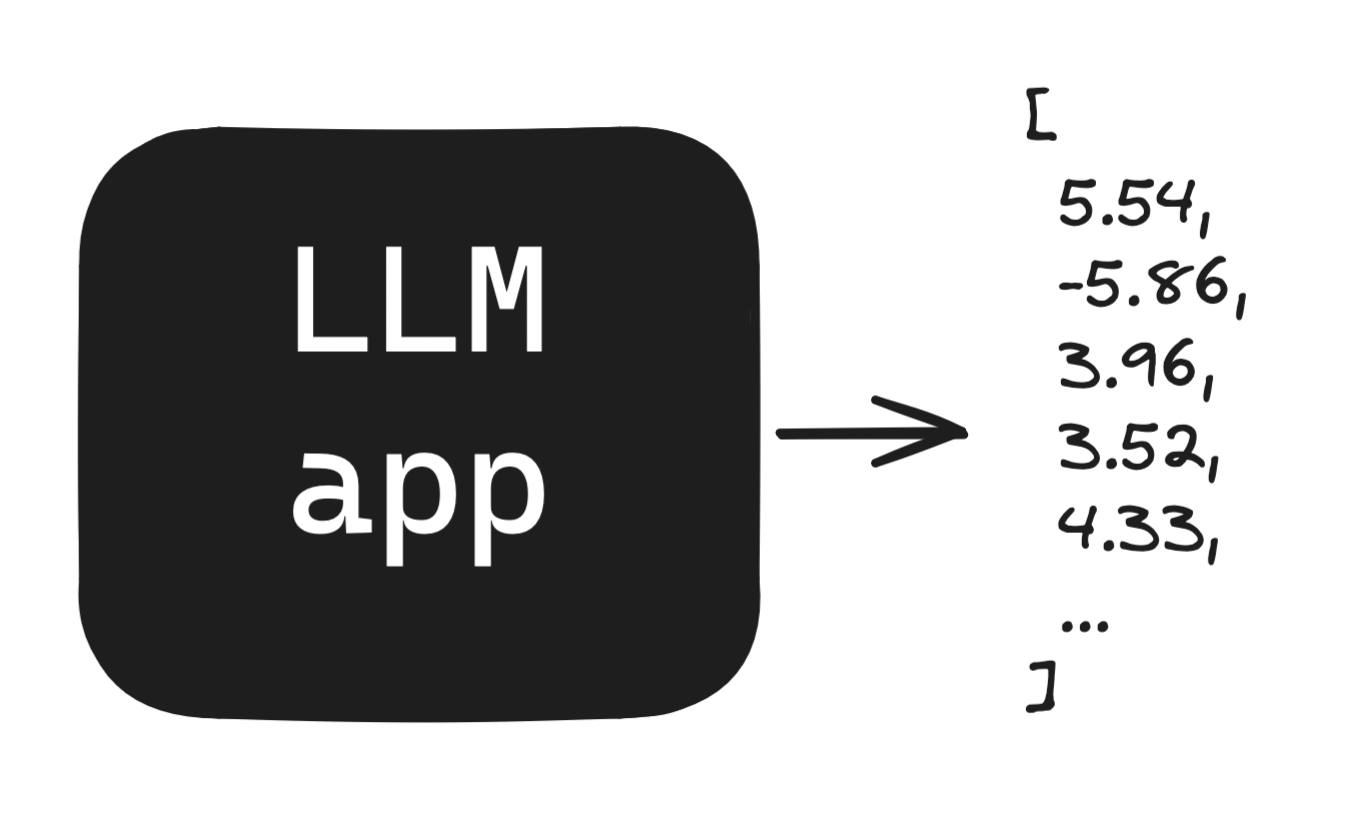

Sampling is concerned with the decoding part of this diagram. Models generally work in the following manner: Given some inputs, do a bunch of math, get some arbitrary scores as outputs.

On their own, these scores are meaningless. We often normalize them using a function called softmax which let’s us interpret them as probabilities.

ℹ️ What does interpret them as probabilities mean?

The softmax function sets all of our values to be between 0 and 1, with the constraint that all of these numbers sum to 1. This is also true of probabilities. That said, there aren't constraints to calibrate these probabilities: A token with a softmax output of0.66 may not actually be correct 66% of the time. I'm most comfortable calling these probabilities, psuedo-probabilities, though some people use confidence scores. I use probabilities throughout this piece as the visualization app's sampling is properly calibrated.

Choosing a prediction

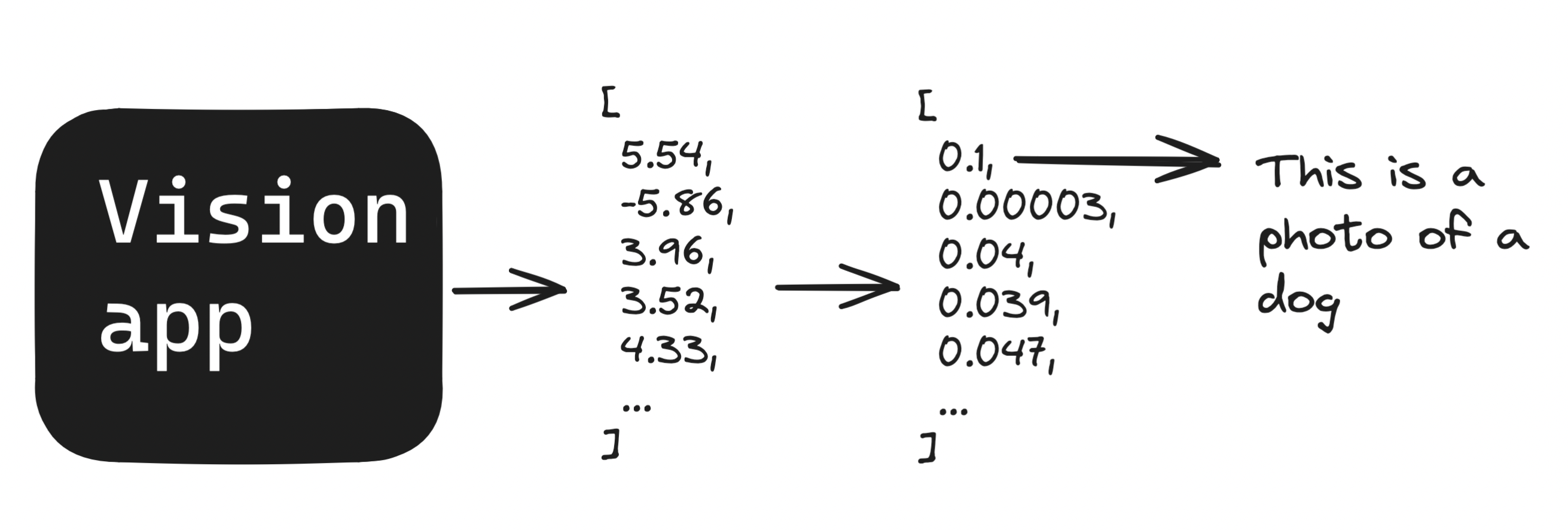

Let’s step away from the ChatGPT example for a second. Consider a classification problem: An app that identifies what’s in a photo. How do we go from a model generating probabilities to a prediction? That’s simple enough: Given an array of probabilities, pick the biggest one.

It’s tempting to think this approach will work for our language model, too. We have one big difference to worry about, though: Language models consume their own outputs. In the case of GPT2 (analyzed in this paper), we can output any one of 50,257 tokens (which are sometimes entire words, sometimes parts of words, and sometimes characters like ..

To generate an answer like print("Hello world!") in our example above, the model does soemthing this:

How do I write hello world in Python?->\r(new paragraph)How do I write hello world in Python?\r->printHow do I write hello world in Python?\rprint->(How do I write hello world in Python?\rprint->("HelloHow do I write hello world in Python?\rprint("Hello->,

…And so on.

Each output we select when decoding becomes the input to find the next entry in the sequence. We call these types of models autoregressive.

Motivating sampling

What happens if a language model maximize scores like a classification model? The model will often wind up in a loop, where the most probable predictions lead us back to a token we’ve already generated, which leads us back…and so on. From Figure 1 of the paper:

The Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM/Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México/Universidad Nacional Autónoma de…

We want this model to generate probable, meaningful langauge. One of the fun things the paper does is start with the question: What does the distribution of words in language usually look like?

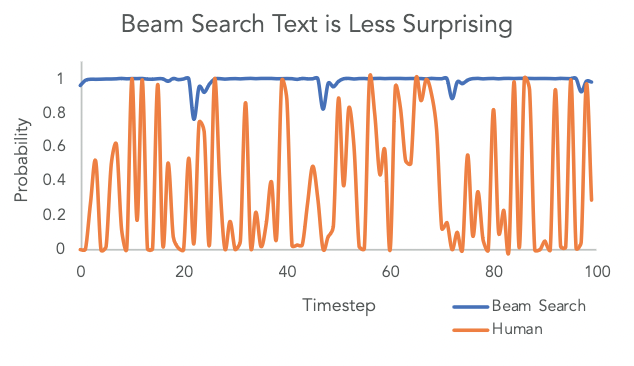

The authors compare actual written text with what a score-maximizing approach would predict, and the results look nothing alike as shown in Figure 2:

Real language is pretty random! It follows that for generated text to look like real langauge, the decoder should randomly consider other options than just the most likely ones. We call this sampling.

Sampling methods

Random sampling

The simplest sampling method is sampling according to computed probabilities. For example, a model outputs some score, and the softmax function converts this score to 0.66. We can use a function to generate this token 66% of the time. Let’s do exactly that!

In the application below, you can choose between two prompts:

"The greatest basketball player of all time is...""The car is..."

I made up some possible next words for these prompts, and I made up some scores for those words. The first prompt has a high-variance output (a peaked softmax) and the second prompt a low-variance output (a flat softmax). While these initial scores are arbitrary, this app computes sampling functions and transformations in real time.

There are two ways to interact with this app:

- You can change the prompt with the radio buttons

- You can draw samples with the Generate the next token! button. (Note: Greedy sampling would always select the biggest number(s) here.)

In practice, sampling totally randomly causes generations to diverge too much to be useful. Researchers have suggested some modifications to improve this.

Temperature

We may add a parameter called temperature to modify the distribution of computed probablities. Temperature ($t$) is a scaling constant that is set to a non-negative integer. Temperatures between 0 and 1 exagerate differences in the results, while temperatures larger than 1 downplay these differences.

Let’s add a third input to the app: a slider for temperature.

Temperature can help shift softmax distributions around, but in practice we don’t know the shape of these distributions for each input or prmopt. People tend to set temperature by guessing and checking for some results.

Top-K sampling

What if we want to be a little more extreme than temperature, and only consider our most-likely predictions? This is called Top-K sampling, and can improve sampling.

Top-k sampling takes the top scores at each step, sets everything else to 0, and rescales those top k values them with another softmax transformation to generate a new set of probabilities. Put another way, we prevent the model from generating anything other than, for example, the 5 most likely tokens.

I’ve added a fourth input to this app: A text box for inputting a value for K. Try it out with each distribution type for 2, 3, and 4.

Okay, now follow my lead here. Set temperature equal to one, K equal to 3, and swap between our two prompts.

While we may be happy to only consider the top 3 predictions for the peaked (basketball) prompt, this leaves out fine predictions for the flat (car) prompt. The top 3 predictions for the basketball prompt are responsible for 99.62% of our probabilities, but the top 3 in the car prompt gives us a much smaller 63%.

This is precisely the problem. We don’t actually know the shape of these distributions and a value of K that is appropriate for one distribution may be inappropriate for another.

What if we could infer approprate values of K from the data? This motivates nucleus sampling.

Top-P (nucleus) sampling

Let’s return to the paper directly:

The key intuition of Nucleus Sampling is that the vast majority of probability mass at each time step is concentrated in the nucleus, a small subset of the vocabulary that tends to range between one and a thousand candidates. Instead of relying on a fixed top-k, or using a temperature parameter to control the shape of the distribution without sufficiently suppressing the unreliable tail, we propose sampling from the top-p portion of the probability mass, expanding and contracting the candidate pool dynamically.

One note here on scale: The authors are testing the model GPT2 in this paper, which has a fixed vocabulary of 50,257 tokens. Therefore these neighborhoods (or nuclei) of probable candidates are at most 1000/50257~1.99% of the possible results.

I find it more helpful to think of nucleus sampling as top-p sampling. Similar to top-K, let’s set unlikely tokens to 0 before we sample; but unlike a fixed top-K, let’s consider a dynamic threshold based on the sum of computed probabilities.

I’ve added a fifth and final input to the app: A slider for setting top-p. I’ve tried to visualize how top-p is computed by displaying our cumulative sum of computed probabilities as well as where p lands in this space.

The authors find top-p sampling to perform very well with p=0.95. They do not scale temperature in their nucleus sampling experiments, so this saves a ton of effort in manual tuning.

Closing

That’s what I’ve got! I enjoyed writing this a lot. Getting these examples to work in JavaScript looks nothing like the PyTorch (or other deep learning framework) code, so I feel like I learned this twice. If you’re still curious about this space, I highly recommend reading the paper yourself, I skipped a lot of the good parts.